Click through to Best of 2020 to discover the Newsworthy articles with greatest impact: whether by highest page views, social media engagement or reportage on important social issues.

COMMENT

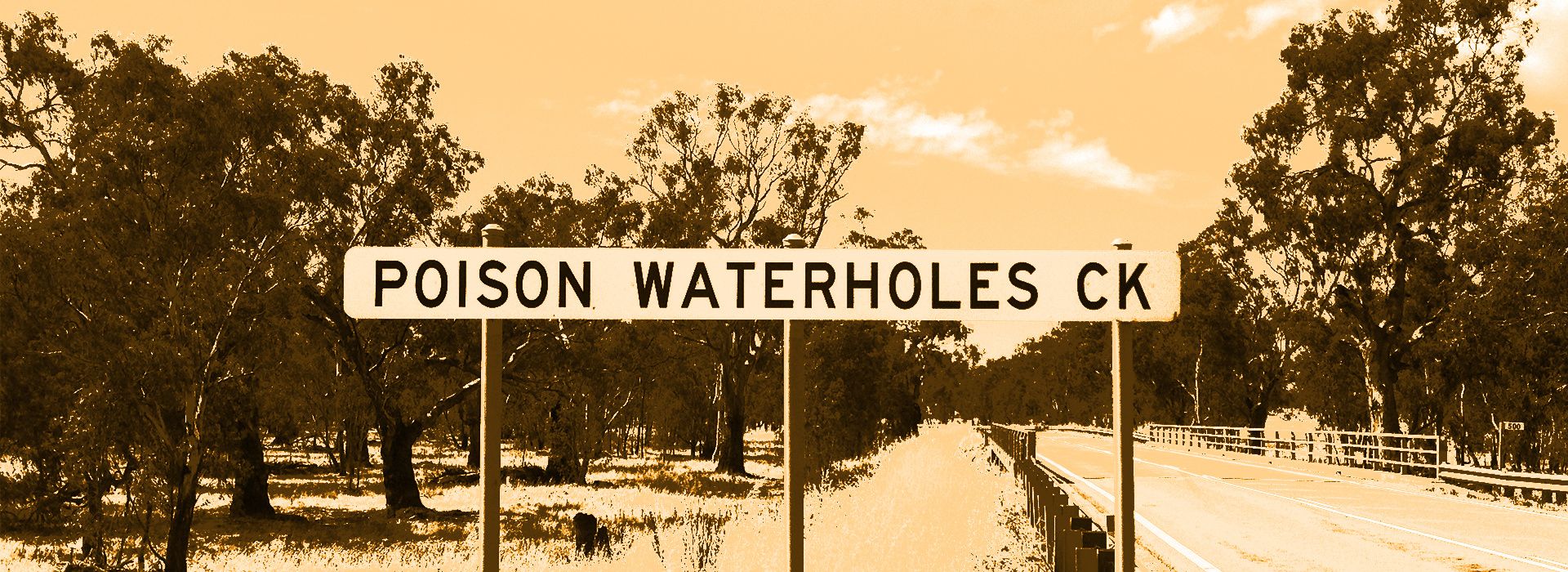

I first saw it heading west towards the Hay Plain, about 10km west of Narrandera – a small creek which bore a strange name, Poison Waterholes Creek.

This small roadside sign kickstarted a journey of discovery for me, to uncover why a creek in the middle of nowhere, would be associated with poison.

My research led me to an article by Indigenous journalist, Stan Grant, who described a history unknown to me: of warriors, slaughter and revenge that played out in the frontier clashes of the early 19th Century. For the first time, I learned of Windradyne, the Wiradjuri leader and warrior who courageously waged war against the early settlers and missionaries.

Grant, a proud Wiradjuri man, explained the waterhole was a popular resting place for the Wiradjuri people until a "local homestead owner grew tired of the black people on his property, so he poisoned their waterhole".

The name references a dark period of Australian history. Some argue the name "leaves a poisonous legacy" and have called for the name to be changed but to have it scrapped would ensure this history is forgotten. Grant concludes his account with a call to retain the sign, to "keep our stories alive. To understand. To forgive."

This got me thinking about the current debate around tearing down statues and the role history plays in determining our identity, of what is commemorated and remembered and what is not?

The victors write history. Statues around Australia and the world commemorating colonial or slave-related figures emphasise this. But does that mean we must tear them down if we are to effectively confront our past?

The killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police on May 25 has sparked an unprecedented demand for action against systemic racism across the globe. "Black Lives Matter" has become an ongoing rallying cry as hundreds of thousands take to the streets. (A second Sydney Black Lives Matter protest was banned last week due to public health concerns.)

As the protests flow across our continent and around the world, controversial statues have been targeted, graffitied and removed. Activists are mobilising and forcing everyday citizens – from former colonial powers such as Britain, France, Belgium and colonial nations like the United States, Brazil and Australia – to reconsider the history behind their monuments and in many cases, to confront dark moments of their colonial pasts.

But should these statues be torn down? History is riddled with injustice and there has always been a tension between preserving historical memory and glorifying past wrongs. Does tearing down all statues with any unsavoury reference to racism help us tackle current injustice within our countries?

To effectively confront our ugly past, perhaps we need to look into why the statue was erected in the first place and try and understand the values of that time. In Britain, Winston Churchill's statue in Parliament Square, Westminster was constructed to commemorate the former Prime Ministers' role in defeating Nazi Germany and fascism, not to glorify his racist inclinations and controversial opinions. Despite this, Churchill's statue has since been tagged with the words "was a racist".

In the two months since Floyd's death reignited the Black Lives Matters movement, statues of Captain Cook have been graffitied with the words "sovereignty never ceded" and "no pride in genocide". A petition for the removal of the statue of Cook looming over Cairns has garnered over 15,000 signatures.

Two women have been arrested after the Captain Cook statue in was defaced with spray paint, and busts of Australian… https://t.co/oVY1tY2x9s— news.com.au (@news.com.au) 1592095020.0

People are angry, hurt, and wanting to learn more about our fraught past. We must look back with clear eyes and reconsider how we define ourselves as a nation but the destruction of artefacts that serve as a confronting reminder of that past will not solve the real issue.

Jerome de Groot, an historian based in Manchester, UK, says "history happens in public and the memory enacted in parks, squares and streets are important for the way a polity defines itself. How and what a nation chooses to remember, the strategies for commemoration and the implications for acts of memory; these are all deeply important and immediate issues for citizens of those states to engage with."

For de Groot, statues are important artefacts of a time gone by. Erasing the dark narratives of history do not fix a generationally entrenched problem. Worse, we risk air-brushing a critical part of our evolution as a society be it good or bad.

In Australia, the absence of Indigenous monuments or statues implies a gap in our history. We need to alter the way we choose to remember if we are to accurately understand our past, which brings me back to Poison Waterholes Creek.

Instead of tearing down existing statues or signposts to history, we should rather focus on the gaps in our history and look to commemorate those Australian heroes who have not yet been properly acknowledged. Figures like Windradyne who, if not for that sign across the creek may have remained to me, a ghost of the past forever.

Ruby has a Master's degree in Media (Journalism and Communications) from UNSW (2019-2021). She works for a not-for-profit organisation and enjoys reading and history.

Afraid of an egg: the tyranny of living with social media's body standards