- Winner of the 2021 Ossie Award for the Dart Centre for Journalism and Trauma, Asia Pacific, reporting on the impact of violence, crime, disaster and other traumatic events

- Click through to the Best of 2021 to discover the Newsworthy articles with greatest impact: whether by highest page views, social media engagement or winning national awards.

When your pursuit for a better world poses a political threat, do regret and tears find their way behind the bars that imprison you? I asked my father: "What is it like to be a political prisoner?"

It's Sunday morning, August 15, 2021, and like the rest of the world I have just woken to an Afghanistan under Taliban control. It's all over the news. Every second post on social media is pictures and videos of the event unfolding.

Kabul fell without a single shot fired, without any resistance from an Afghan national army of "300,000 men ready to defend the country", according to the Biden Administration. The Washington Post reported within a little more than a week, "Taliban fighters overran more than a dozen provincial capitals and entered Kabul with no resistance". Afghanistan's president fled to Uzbekistan.

Insane. Don\u2019t have any other words. \n\nThe Kabul Airport.pic.twitter.com/ylraJsDyme— Rag\u0131p Soylu (@Rag\u0131p Soylu) 1629106523

The Taliban replaced the US-backed administration, which seemed to almost melt away, with the new Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. This "replacement" process is what people fear, the process of regime change, a process the Taliban has referred to as cleansing, of destroying anything which they deem impure and purifying that which can be saved.

Doyle Quiggle, who served as a professor to US Troops at a forward operating base in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, has written at length on how the Taliban "weaponised moral authority in Afghanistan", arguing they "manipulated the cultural-biology of disgust which is highly primed in members of honour-shame cultures". He went on to suggest that a Taliban fighter is today motivated by a "disgust-contamination" pathology where anyone who is not Taliban is not a pure Muslim, and therefore disgusting and contaminated.

Quiggle focussed on Afghanistan's tribal cultures but this disgust-contamination pathology is prevalent in all circumstances where a race, ethnicity, religion or ideology perceives itself supreme. This is true for white supremacy. It is also true for the Euro-American interventionist policies which hold that Western democracy must be exported to help more "backward" societies.

These nuances in the supremist psyche of fundamentalists are what Afghans on the ground would be intuitively aware and extremely fearful of. This is why they were willing to cling to planes to try to escape the Taliban.

As an Iranian, I can speak to this fear. This type of Islamic "puritanism" is exactly what we went through after the country fell to Islamist fundamentalists in 1979. The number of political prisoners and dissidents killed inside and outside Iran in the past four decades has been estimated to be as high as 90,000. In 1988 alone, 30,000 prisoners were killed in the space of eight weeks. Christina Lamb wrote in 2001 about how "children as young as 13 were hanged from cranes, six at a time, in a barbaric two-month purge of Iran's prisons". On September 17, the Iranian diaspora around the world will once again remember their fallen on the 33rd anniversary of that massacre.

I connected to the fear many Afghans are feeling as I watched, with astonishment and despair, the chaotic scenes at Kabul airport. Whilst scrolling through the mayhem, a call from my father appeared on my screen. I picked up. "Hello?" He stayed quiet for a moment. "Hello, Baba?" With a voice on the verge of trembling, my father asked: "Are you watching this? Do you know what's going to happen? Do know how many of "them" there will be?"

By now I know exactly who he is referring to when he says them. In the aftermath of every coup, every revolution, every type of regime change, even in negotiated transitions of power, there will always be a huge number of "them" – political prisoners. They are prisoners amassed from within those groups which the new regime considers a threat. No forceful transition of power, regardless of type or form, will ever be without a "them".

This has been especially true in modern history. In the aftermath of 1789 French Revolution, more than 16,500 political opponents were beheaded by guillotine. In the centuries since, violence against political opposition has been normalised: by Stalin with Russia's gulags, by imperialists in the Belgian Congo, by Mao in China's Iaogai reform labour camps, by Latin America's military juntas and by Iran's Islamic Republic.

The elusive 'them'

The political prisoner or prisoner of conscience is an elusive figure. They hold no consistent definition. They have been loosely defined as "a person who is imprisoned because that person's actions or beliefs are contrary to those of his or her government." Amnesty International uses the term to describe "any prisoner whose case has a political element – either in the motivation of the prisoner's act, the act itself, or the motivation of the authorities in their response".

There is another benchmark, the one by which political prisoners themselves distinguish their ranks. It is based on the degree of resolve within the heart and mind of each political dissident to resist their oppressor. This level of resolve will usually determine the fate and future of the prisoner – the greater the resolve, the greater the detriment.

Whilst the United Nations has tried to guarantee global civil, social, economic and political liberties by setting them out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, sovereign states are constantly working to contest and undermine the definition of a political prisoner by reinventing the terms they use to suit the authority of the day.

In response to this, international human rights organisations such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch actively work to encapsulate and where necessary redefine the term whilst at the same time campaigning to regulate the behaviour of such states with regard to their dissidents.

Political prisoners are fundamentally different to the common criminal. They are individuals who find strength in altruistic ideals. They see themselves not as individuals but as atomic parts to bigger causes and therefore are willing to resist by extraordinary means viewed as necessary – even in the face of degradation, torture and executions.

Because of this, they are viewed as significant threats – especially to those states that do not welcome challenges to their authority and/or endeavour to rule through corruption, oppression and suppression. Such states are yet to provide what the United Nations regards as "first generation" rights, to their citizens.

This doesn't mean Western democracies can wash their hands clean of the subject. Some of the most famous political dissidents and prisoners belong to us: Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. The Alliance for Global Justice website has a comprehensive list.

Critical political minds are deemed to be specifically dangerous to the authority of a newly formed state – especially if that state consolidates power by force. This is because the environment is still fragile and a variety of forces and ideas are still competing for position and power. Accordingly, active individuals are rounded up and imprisoned in swift and uncompromising crackdowns. They are then systematically broken down through violent interrogation and torture until they give in, and as a result, give up other dissidents.

There are no white revolutions, only bloody red ones

The day Kabul fell, I tried to reassure my father, saying doubtfully that the Taliban had announced there would be no revenge, no retribution.

"There are no white revolutions," he replied, "only bloody red ones." He uses the term revolution loosely for the sake of the saying, in reference to the transition of power in Afghanistan.

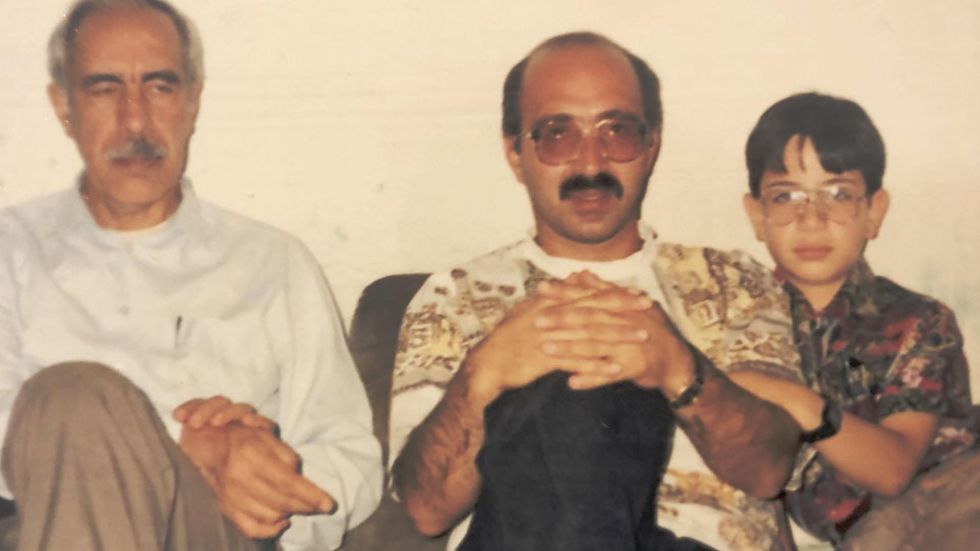

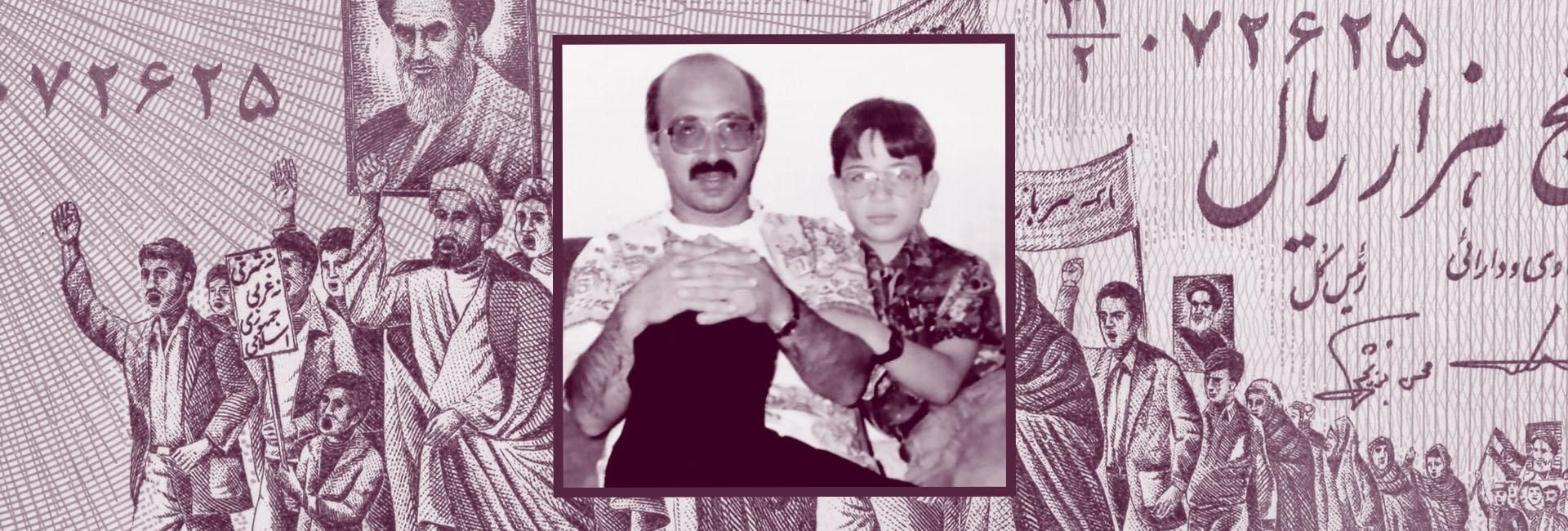

He would know, my father served 11 years in total in some of Iran's most notorious prisons. My mother served seven years.

My parents don't like to speak of their experiences, but the collapse of Kabul was one of those rare occasions where my father opened the vault slightly on memories he usually keeps locked away. They were both held in Iran's notorious Evin Prison. Until this year, no outsider had seen images from inside the prison. On August 24, for the first time hackers released footage from inside. Both aNews Turkey and BBC reported on the vision. BBC Persian's correspondent Jiyar Gol reminded the audience that the leaked videos only confirmed what former political prisoners had been claiming for decades.

Hacked footage from security cameras in #Iran\u2019s Evin Prison and the publication of some of the prison\u2019s documents published online by a group of hackers \u201cEdalat-e Ali\u201d (Ali\u2019s Justice) revealed a fraction of the crimes committed in Iran\u2019s prisons.\n#Evin\nhttps://iranfreedom.org/en/2021/09/07/leaked-video-of-irans-evin-prison/\u00a0\u2026pic.twitter.com/ntOCeo1RC4— Mitra Motamed (@Mitra Motamed) 1631047802

"Former political prisoners say the footage is nothing compared to what they experienced in detention. They accuse authorities of routinely using sexual, physical and psychological torture," Gol said.

Did my father ever regret being inside Evin prison? "No, I knew why I was there," he said with unwavering certainty. "Was I ever scared? Yes, but when you believe in your cause, there is no regret. You either live for something or you don't."

Yet, with the release of the Evin prison footage, their long ago past becomes present, and I worry about my father, but even more so, my mother. Unlike my father, my mother didn't quite make it through those years. The pain pervasively stayed with her. Being female on top of being a political prisoner under the Islamic Republic regime, compounded the effect.

Having experienced the horror, my mother, like many former political prisoners, seems to rehumanise the dehumanised. She connects to the suffering of those experiencing the distress, by reconnecting to the memories of her own experience and is retraumatised.

To manage her demons, my mother tries to completely avoid anything that may take her back there but it can be hard to avoid. My sister found her weeping recently, watching news of the sentencing of Hongkong's latest political prisoner Tong Ying-kit, jailed for nine years in the territory's first national security law trial.

UNSW psychological scientist Brock Bastian has researched the connection that occurs through shared adversity. He says that "pain is a particularly powerful ingredient in producing [such] bonds". The Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou called it "the common pain".

My parents both have an extremely intense time engaging with news surrounding political tension and instability, especially civil wars or anything resembling revolutions or uprisings. Regardless of geographical locations, it all seems to hurt.

I have observed them respond in a similar manner to different events over the past decades – from Assad's dungeons in Syria to Erdogan's crack down on the intellectual class in Turkey, to the quashing of Hong Kong's uprising by China, and now, Afghanistan.

I've learnt there is a collective pain that connects political prisoners across the world, almost regardless of ideological inclination. It is the manifestation and persistence of various forms of dignified human desires – in the face of a power that tries to suppress it violently – and its subsequent resistance.

My father's only fear

When I spoke to my dad on the Sunday as the Taliban swept into Kabul, he was in a state of shock. The next time we spoke, he'd moved past shock to anger.

"Do they know how many people [the Taliban] will kill? Do they care? Another 10, 20, 30 years of girls without education. Do they know how many people will be tortured? how many will rot in cells? Do they care? After 20 years they just leave them to the wolves?"

Speaking of his time in prison is hard, he deflects with bad dad jokes or when he does recount anecdotes, furnishes them with the barest of details. On this day, he pushed through his post-traumatic stress to tell of the mock executions he and his fellow inmates endured.

"They would take people all the way to the noose, pull the stool from under them but catch them just in time to watch them urinate their pants. And then they would interrogate them again – with the warning that 'next time it would be for real'.

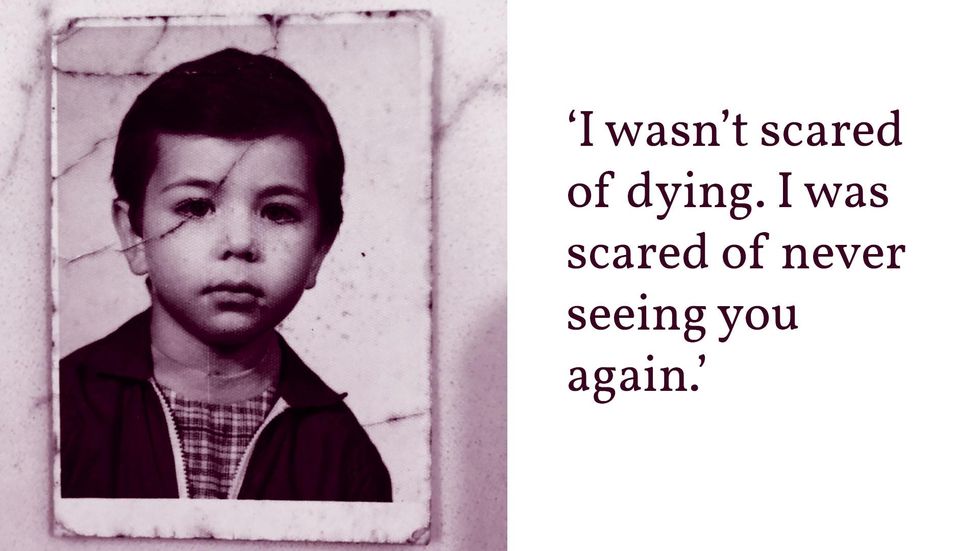

My parents didn't get to witness the first seven years of my life. I have always wondered, did my father ever feel any regret for this loss, even if he did not regret being imprisoned for his cause? I have wondered, did my father ever feel guilt, for not being able to watch me grow?

He pauses for a moment, thinks, then says "of course I did, but I would have felt even worse if I renounced my beliefs and got out that way. What would I be able to say to you, my son? That your father sold out on his convictions?"

I was taken aback by my father's answer and privately wondered what would I have preferred: To have that father then? Or this father now?

My father never sold out his convictions. So, I asked, given what he had to endure in holding to that resolve, was he ever scared of death? He looked up at the ceiling and his composure almost cracked, then only a sigh punctured his throat. He is trained in the martial art of silence. He holds on now like he did then under torture. "No, I wasn't scared of dying. I was scared of never seeing you again."

In Iranian dissident culture they call them setareha, which means stars – political prisoners are small, bright particles of light, against the eternal mass of darkness.

This is what my parents are and always will be – ye setareha – small, but not insignificant, particles of light.

As a checkout chick, I'm used to rudeness. But I can't bear the threats and violence