- Andre was named 2020 Walkley Student Journalist of the Year (All Media) for his two-part series on Rwanda – 'The dark side of Africa's poster child' and 'Who wins when Rwanda plays the 'genocide guilt card'

- Winner of the 2019 Ossie Award for student journalism for best text-based story by an undergraduate student (over 750 words).

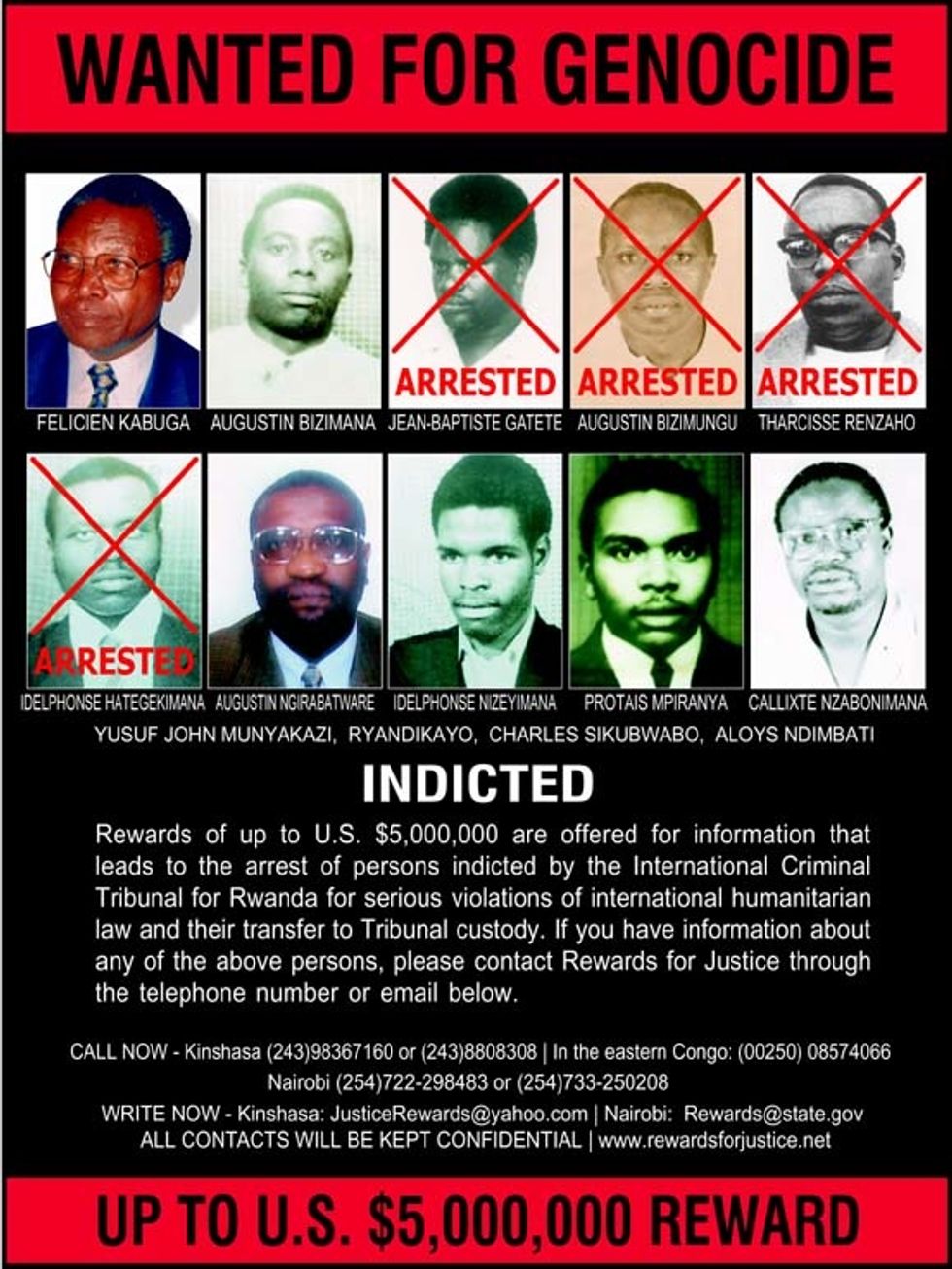

Crossing the border into one of the smallest countries on the African continent, you are immediately confronted by 'Wanted' posters from an event that irrevocably changed this nation 25 years ago.

The bounty signs, which evoke America's Wild West, offer rewards of up to US$5 million for the capture of Hutu men still wanted for their genocidal crimes against the Tutsi minority. Welcome to Rwanda.

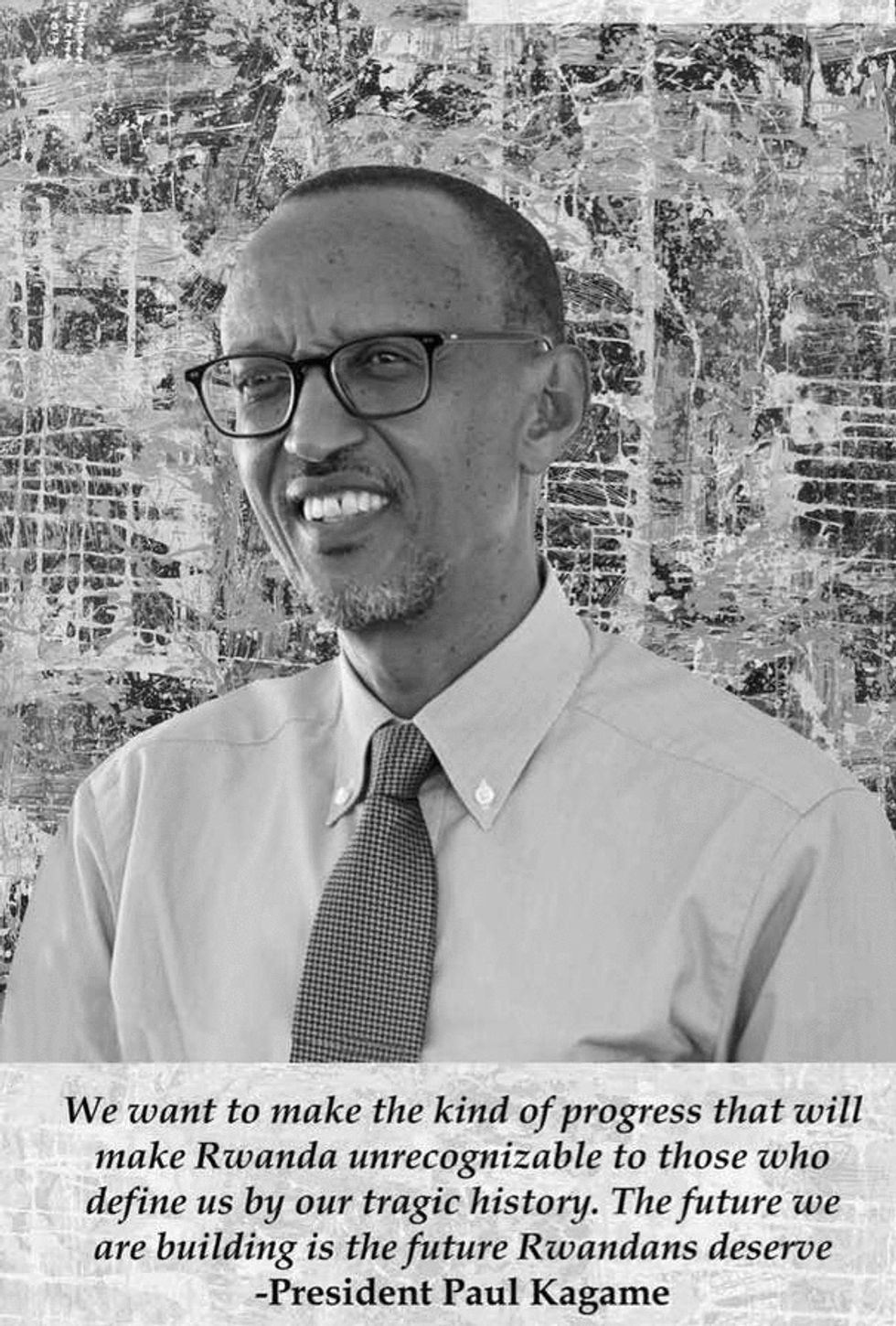

From the depths of a murderous four-year civil war that culminated in the 1994 April-to-July genocide, where the government estimates up to 1 million lost their lives, Rwanda has emerged as an unlikely African success story. It is the little country that could bind its terrible wounds, psychological and physical, and move forward. Forbes calls it a "poster child for progress" and last year the World Bank commended its "high growth, rapid poverty reduction and reduced inequality", attributing this to strong government-led economic policy.

'In Rwanda, the police don't even take bribes!'

But could it be true? After studying Rwandan society and politics at university, I wanted to see this modern-day economic and social miracle for myself, to better understand what had been achieved. In 2018, I spent eight months in sub-Saharan Africa with more than a month of that time in Rwanda, navigating the winding backroads, camping out in rainforests and on volcanic hillsides, speaking to everyday Rwandans in remote villages, as well as the city dwellers, about the genocide and the progress made since.

Peace and prosperity, at a price

Photo: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Twenty-five years after the genocide, the manhunt for leaders of the genocide continues.

What I found surprised me. Here was a nation with a government that had held power for 25 unbroken years following a mass ethno-conflict yet everyone was apparently happy with the government and were united regardless of ethnicity. Despite the obvious physical evidence of the genocide still on show – men and women with large machete scars across their temples, amputated limbs and other disfigurements – every citizen I met had only positive things to say about life in Rwanda today, their president, Paul Kagame, and his Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) government.

In Kigali, Rwanda's capital city, I met Moses*, a genocide survivor who went on to found a community-based organisation educating street children. "Before [the genocide] we had poor authorities," he said. "They wanted to divide us. To make it so we only saw the differences in each other, between the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa, not what united us."

"My brothers died in the genocide but now we have better authorities that have made sure we are at peace and together as one people."

Repeatedly, I heard stories from men and women who were the sole survivors of families massacred, who insisted that now all Rwandans had reconciled after the primarily Hutu-led killings.

Only one man I met in Rwanda suggested a counter to the narrative: a Burundian national who lived in Kigali but said he didn't "feel as free here". In his home country, tensions remain between the ethnic Hutu and Tutsi, which influenced his decision to move. "I came here for security and for a job. That is the positive side of being here, at least there is more safety."

Even before arriving in Rwanda, I had been told of the economic and social miracle. Kenyans and Ugandans who had visited told me that there was no country like it in Africa. In Kenya, a local student from the University of Nairobi, spoke with awe at the lack of corruption.

"In Rwanda, the police don't even take bribes!" he told fellow students, who refused to believe him. In a continent where rubbish often piles up in the street, Rwanda had instituted a monthly community clean-up day for all citizens to pick-up rubbish in their designated areas.

It all adds up to a remarkable national resurrection narrative. Dr Filip Rejntjens, Professor of Law and Politics at the Institute of Development Policy and Management, at the University of Antwerp, has focused on the region for over three decades. He acknowledges post-genocide Rwanda's achievements but calls this often-repeated narrative of good governance, peace and reconciliation, a "public transcript" everyone must follow.

"All Rwandans know it, from the minister to the peasant… they know that this is the discourse we need to formulate because otherwise we get in trouble," the Belgian academic, who is banned from re-entering Rwanda because of his commentary, said via a Skype interview.

'I wouldn't even assume there's reconciliation in Rwanda. I think there has been a silencing.'

Despite its burgeoning economic development, Rwanda's population still lives for the most part, outside its cities. Hiking through banana plantations, I asked villagers in French, the old colonial language, about this purported government suppression. The villagers I met were curious but cautious and seemed wary when I posed my questions. In one instance, when I specifically raised the question of a "public transcript", a group of elders forced me to leave their village.

"You cannot do this," one said to me. "Leave here, you will only cause us problems."

The villagers were reluctant to talk and the government does not want outsiders talking to them, as Dr Susan Thomson discovered. The Canadian academic and author of Rwanda, from Genocide to Precarious Peace, has focused on Rwanda since before 1994 and witnessed some of the genocide first-hand. Her research project had been approved by the government but was stopped in 2006. At issue was the fact she "had spent time talking to rural farmers – what they call 'peasant people' – and therefore had wasted [my] time". She said she was put in a "government re-education camp" and told to "learn the truth" about Rwanda. Through that process it became clear she would not be able to return to the country.

She questions the narrative of reconciliation, calling it a myth. "I wouldn't even assume there's reconciliation in Rwanda," said Thomson, via Skype while visiting Cape Town, South Africa. "I think there has been a silencing."

Human Right Watch's World Report 2019 reports that individuals critical of the Rwandan regime had experienced "arbitrary detention, ill-treatment and torture". It had previously documented in 2017 instances of cross-border assassinations and enforced disappearances.

Reyntjens calls it the "two faces of Rwanda". One part he says, is "the undeniable success of the current regime in fostering 'development'. In terms of socio-economic development and bureaucratic governance this country is performing better than the African average.

"On the other side of the coin is the extreme danger in destroying all these achievements because the violent political governance, leaving no political space, is creating such a great deal of frustration and fear. People simply cannot speak their minds."

In a rare glimmer of hope for free speech, charges of insurrection and forgery against opposition leader Diane Rwigara, 37, were dismissed last December. She had spent more than a year in jail after being barred from running in presidential elections.

The Rwandan government did not respond to Newsworthy's request for an interview by the time of publication.

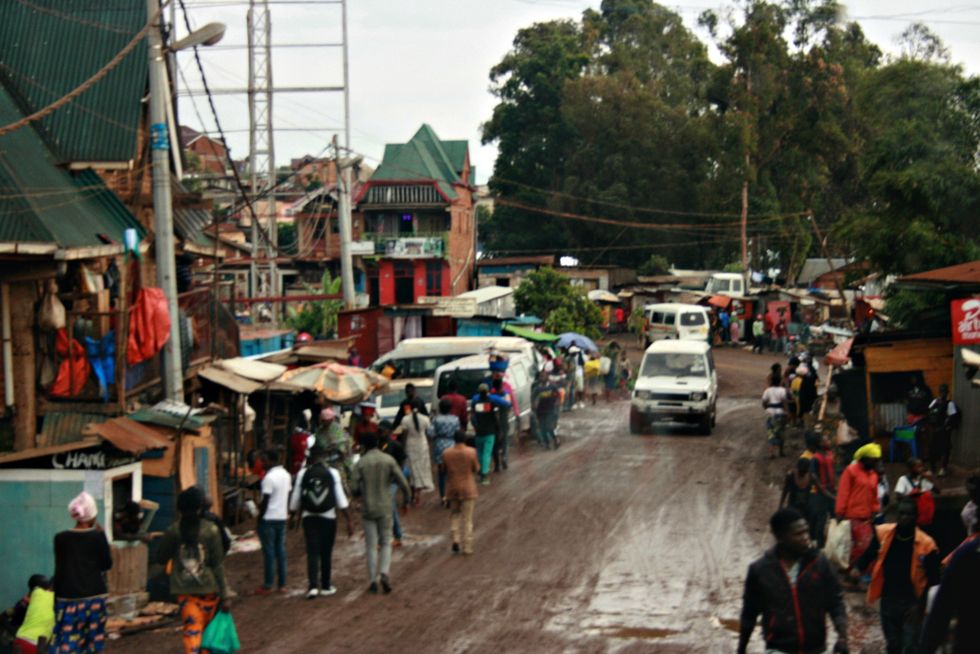

Leaving Rwanda, via a short one-lane bridge at Cyangugu, I arrived in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa. I was interested to hear how they saw their little neighbour, now the rising star of Africa. My Congolese driver Pat had no sooner picked me up at the border than he jumped into a conversation about politics. "Do you see that house? That is our governor's house. He is the one stealing all our money."

Asked to compare the politics of Rwanda to the DRC, he said: "If we had a president like Kagame then things will be okay here. But Rwanda is small, so, he can do whatever he wants and no one fights back but Congo is too big.

"Rwanda is doing well with the jobs and these things. But the difference between Congo and Rwanda, we can say what we like. About politics, about whatever. In Rwanda they must be careful."

In the rare case that a Rwandan would acknowledge the issue of government repression, it was seen an acceptable price to pay for the country's success.

"There are a lot of secrets in our government, but we don't really mind," says Arianna*, 20, a university student who attended the Belgium School of Kigali, alongside children of senior government officials.

"I think we are the best country in Africa now, despite not having many raw minerals. Our economy keeps growing and there is no corruption. Now we are happy that we have good government agencies that give hope and opportunities to the youth so that we all aren't farming out somewhere and so we can become teachers and engineers and more."

"The main thing for us Rwandans is that we are at peace. Twenty-four years ago we suffered. Our families suffered."

Cultural ping pong: Dancing on the edge of two worlds