In Chinese traditional medicine lore, a remedy is only effective if it is bitter.

As I open the door to Kan Wah Chan’s clinic, the strong smell of Chinese herbs comes at me from all directions, up my nose, through my mouth, into my lungs, making me feel like I’m breathing in a giant medicine furnace. Four floor-to-ceiling wooden cabinets cover an entire wall. The two on the left display rows of large glass jars filled with flakes, blocks, filaments and strips, mostly yellow or brown in colour. On the right, the rows of glass jars are smaller, each neatly labeled with herbs such as di ding, lotus leaf and loofah. A dozen large cardboard boxes stacked besides a glass counter, boldly marked "Fujian Herbs", stand waiting to be unpacked.

In front of the glass cabinets, an Asian woman grabs a handful of danggui, placing it carefully on a small brass tray attached to the scales with three thin brass chains. With her left hand, she picks up a copper chain with a thin red-brown wooden bar attached. The other end of the bar is engraved with white dots to indicate weights. Her right hand moves across the small scale; seeking the balanced midpoint, she leans closer to squint through her gold-rimmed glasses to see where the scale has balanced.

As I watch, a sudden tearing sensation in my abdomen blocks out the strong medicinal smell and the room becomes hot. In a few seconds, my back is drenched in sweat and a piercing chill spreads upwards from my feet. Realising I’m about to faint, I quickly grab the chair to my right and fall into it. This has been going on for three days, and, after intense vomiting and my body temperature continuously alternating between hot and cold, I'm hoping traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) will help.

Finally, I hear my name called. "Next, Tina."

To this day, Chinese people's trust in traditional medicine is dependent on the age of the practitioner.

I heard about Mr Chan’s TCM clinic, in Chatswood’s business district, in northern Sydney, from a friend. It sits on busy Victoria Avenue, where shopfront signs in English are interspersed with striking Chinese-language signs advertising pearl milk tea, fried dumplings, Chinese-style restaurants and at least a dozen Chinese medical centres. On the median strip, rows of white market stalls display bracelets, calligraphy, paintings and carvings from China. Stallholders switch between Cantonese and English to introduce their wares to passing shoppers.

As you push open the clinic’s small glass front door, the strong smell of herbs hits you. A message in Chinese — "仁心仁术" — greets patients as they enter. The four characters translate as “doctors must not only have excellent medical skills, but also a benevolent heart”.

The six-room clinic is divided into two domains. The first, run by 40-year-old Janet, includes a dispensing room, decoction room where herbal medicine is prepared and storage area. As each new patient arrives, she calls out “someone is coming” in Cantonese towards the room on the right. The second domain, a diagnostic room and two acupuncture rooms on the right, belongs to Mr Chan. (It’s Mr not Dr because Australian law forbids the use of “doctor” for a TCM practitioner.)

"He says very little, but every word is precise," my friend Shirley Liu recalled of their first meeting. The 24-year-old went to see Mr Chan because, after getting the HPV vaccine, she did not get her period for six months, making her uneasy.

Before seeing a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner, Liu went to her general practitioner for a thorough examination, which failed to find a cause, and then to a specialist, who offered her only one solution — take a short-term contraceptive pill, Yasmin, for three months. Liu took the pill home but ultimately didn't take it, opting instead to seek other treatments. She learned about Mr Chan from a colleague.

Stick out your tongue

AFTER briefly asking for symptoms, Mr Chan gently placed his middle and ring fingers on Liu’s right hand, checking her pulse. His gray pupils narrowed, focused on a point on the wall. Five or six seconds later, he took the pulse of her left hand in the same way, Liu said, recounting her first visit to the clinic. During the consultation, gentle piano music playing in the background helped her relax.

Mr Chan looked to be in his sixties, dressed in a dark blue feather vest with a pair of rimless glasses resting on his thin cheekbones. The hair on his head is thick at the sides but noticeably thinner on top and interspersed with strands of silver. His desktop was bare but for a computer screen and keyboard, a pot of greenery and an empty green onyx-carved name-card box.

"Miss Liu, please stick out your tongue," he asked.

“Pulse” and “tongue” examination are the two main diagnostic methods in the "four diagnostic methods" of Chinese medicine. Changes in pulse and the tongue colour are used to identify the functions of the internal organs and to investigate the cause of the disease. The other two are "seeing" and "questioning", which involve observing the patient's face and voice and inquiring about existing symptoms and medical history.

Mr Chan tilted his glasses upward and stretched his neck forwards to look, then nodded, confidently turning to his right and beginning to tap rapidly and forcefully on the keyboard. While he was thinking, his left hand left the keyboard and tapped the desktop with the gentle piano rhythm, then inspiration struck and his fingers returned to the keyboard with powerful taps.

A few minutes later, he produced a printed list of a dozen herbs with the weight of each required. The largest quantity is 20 grams for duzhong, shanyao, tusizi and yinyanghuo and the smallest, for zhigancao, needs only six grams.

Decocting the remedy

HERBAL medicine is the most common means of treatment in traditional Chinese medicine and has been used for more than 3000 years. The volumes of classic early Chinese poetry Yi Jing and Shi Jing both mention dozens of herbs that are still in use. Today, there are close to 450 common herbal medicines, most of which are of plant origin but some may also contain animal and mineral substances.

The ancient Chinese people tended to associate the effects of herbs with their names or other metaphorical concepts. For example, the Chinese meaning of ginseng is "the essence of man" because the root is shaped like a small man and it was believed that this herb would help restore a person’s inner energy. The older the ginseng, the more it is believed to help prolong one's life and this ancient narrative has profoundly influenced the Chinese belief in herbal healing.

Unlike blended and concentrated capsules or tablets, Chinese herbs are compounded in the decoction room on site after a diagnosis. Even for the same symptoms, the herbs prescribed to patients will vary depending on their constitution, gender and age. Practitioners usually prescribe herbs to patients for five to seven days at a time, with follow-up visits once a week. They will make adjustments to the prescription as required; there is no fixed course of treatment.

A herbal medicine usually contains 14 herbs. The herbs are soaked in water for 30 minutes in a ceramic pot before they are simmered for an hour on low heat to evaporate three quarters of the water. The boiled medicine, usually dark brown or black in colour, tastes bitter and is hard to swallow but the Chinese believe that medicine is only effective if it is bitter. They like to use the phrase "good medicine is bitter" to illustrate that harsh criticism or difficult circumstances can be beneficial to people.

Chinese needlepoint

ACUPUNCTURE is an important method of treatment in Chinese medicine. It divides the body into fourteen meridians from the crown of the head to the soles of the feet. Fine needles are inserted into the body to clear energy blockages and facilitate the flow of essence and energy within the body.

Humans have been aware of acupuncture points since the Stone Age. By chance, ancient peoples discovered that if some parts of the body were crushed by stone tools during farming, other parts of the body would change accordingly, so they began pounding on fixed areas with animal bones and bamboo. Later bones and bamboo were replaced by finer silver needles.

"It was a magical experience," said Tracy, of trying acupuncture for the first time.

Tracy, who chose not to give her surname, recalled lying on a small wooden bed covered with a thin white sheet. To her right was a metal iron tray filled with dozens of thin silver needles. The needles were slightly longer than a finger, with one end as thick as a toothpick and the other end as fine as a strand of hair.

Tracy's leg was gently twisted into the proper position by Mr Chan. She doubted she could keep it still for half an hour. He used his thumb, index finger and middle finger to pinch the thick section of the silver needle from the iron tray and gently press it into her ankle. Tracy took a deep breath and let go of the corner of her coat. It didn’t hurt as much as she expected. In fact, she barely felt anything.

Only when there were a dozen needles standing in her legs did a faint soreness begin to pass through her calves. Mr Chan positioned a silver-cased headlamp above Tracy's legs and the needles glowed faintly in the warm yellow light. A wave of warmth flowed upwards from her legs to her belly, then to her shoulders and ears. Before leaving the room, Mr Chan reminded Tracy not to move.

'Australian patients don't think you're unprofessional just because you're young.'

Tracy could hardly feel the silver needles in her thighs but the acupuncture points at her ankle seemed to be disobedient, sometimes jumping upwards suddenly. She focused her attention on her ankle, keeping it as stable as possible and not allowing the jumping points to move it out of position.

After 40 minutes, Mr Chan returned. He leant down and pulled out the silver needles one by one, starting with the ankle. Tracy sat up and got closer, seeing the small, inconspicuous red dots left in the pierced areas.

"Be careful to avoid [letting] the cold wind into your body," Mr Chan cautioned as he placed the needles back onto the iron tray.

While this “cold wind” advice comes from every acupuncturist (and TCM practitioner) the acupuncture technique each one uses can be very different.

Chamy Leung, who is based in Chatswood and has practised as an acupuncturist and herbalist in Australia for more than 20 years, explained the characteristics of the different schools of acupuncture.

The Chinese-style acupuncture usually involves inserting acupuncture needles up to 20mm deep into the skin, while Japanese-style mostly involves a lighter insertion around 2-3mm, which is less painful and therefore more popular in Australia. Different acupuncturists prefer different pressure points, some prefer to use scalp needles and some prefer to apply needles in the ear. Each practitioner also has their own customary technique. Some like to rotate the needles while inserting them, some prefer to prick like a woodpecker. Also, some will flick the needles after inserting them to fully stimulate the acupuncture points, which is called deqi — the arrival of energy.

"There's no right or wrong way to do these styles, but there are many different schools of acupuncture and they all have different techniques," Leung said.

In addition to herbal medicine and acupuncture, traditional Chinese medicine practitioners also use treatments such as tui na, fire cupping and qi gong. This medical system is based on the recorded experience of the ancient Chinese people in their struggle against diseases. The History of Chinese Medicine (Chinese Medicine Press, 2016) explains the underlying principles of "yin yang" and "five elements". The fundamentals of this medical system were developed in the 500 years of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods from 770 to 221 BCE. It would reach its peak during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), spreading to Goryeo (modern-day Korea), Japan and Central Asia.

In Australia, however, it would take another 1000 years for the seeds of Chinese medicine to be planted.

It started with a gold rush

During the 1850s, gold fever brought more than 40,000 Chinese to Australia, including a number of physicians trained in acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine. James Lamsey, born in Canton, southern China, into a medical family, was one of them. Lamsey crossed the hemisphere to the then British colony of Victoria in 1851 and established one of Australia's first Chinese medicine clinics, the Lam Kee Po Hong Tong Herb Shop, in Bendigo in the mid-1870s.

With the enactment of the Medical Law 1890, Lamsey's legitimacy was questioned. In 1892, the Bendigo Advertiser reported an “ALLEGED BREACH OF THE MEDICAL ACT” in which Lamsey was accused of “pretending to be a doctor” in violation of Article XI of the act. The case was dismissed. When Lamsey died in 1912, his robed remains were taken back to China.

Lamsey's apprentice, Ack Hing, who passed the traditional Chinese medicine examination in Canton, took over the practice and went on to become the president of the Bendigo Chinese Masonic Association and president-for-life of Bendigo Hospital. During this period, many herbalists appeared in central Melbourne and in the gold mining towns, but all had completed their studies and training in China before coming to Australia.

At that time, being apprenticed to a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner was the only way to learn the practice in China. Many took on only one apprentice in their lifetime, passing on the practice in a single lineage. Unlike Western medicine, which employs sophisticated instruments to detect the cause of a disease, the traditional diagnosis is based on the practitioner's observation of the pulse and tongue to determine the condition of the patient's internal organs. This requires a great deal of experience, and the slightest mistake may ruin a practitioner’s reputation.

To this day, Chinese people's trust in traditional Chinese medicine is dependent on the age of the practitioner. Whether the practitioner has a relevant degree, is registered and legal, or has an impressive clinic setup is not the most important consideration. Leung recalls Chinese patients telling her when she first graduated: ‘You are so young, do you know how to do it? Don't stick it in the wrong place.’

“Australian patients don't think you're unprofessional just because you're young, as long as you've completed a relevant degree," Leung said.

In 1992, the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology began enrolling students in a Chinese medicine degree, making Australia the first Western country to establish an undergraduate program in Chinese medicine at a public university. Traditional Chinese medicine courses have since been offered at the University of Technology, Sydney and the University of Western Sydney, as well as three private colleges, The Sydney Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern School of Natural Therapies, and Endeavour College of Natural Health.

Unlike Lamsey, who brought traditional Chinese medicine to Australia, both Leung and Chan studied their profession in Australia. Leung enrolled at UTS in the second year the Chinese medicine major was offered, completing a Bachelor of Health Science in Traditional Chinese Medicine in 1999.

Chan returned to the University of Western Sydney in 2006, 10 years after graduating with a Master's degree in Business, to pursue a Bachelor's degree in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Herbalism. He started work as a TCM practitioner in 2008.

With the widespread availability of Chinese herbal medicine and acupuncture in Australia, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) announced in 2012 that it would regulate the registration of traditional Chinese medicine practitioners nationwide. This means that people practicing traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture or herbal medicine in Australia must be registered with AHPRA and approved by the Chinese Medicine Board of Australia.

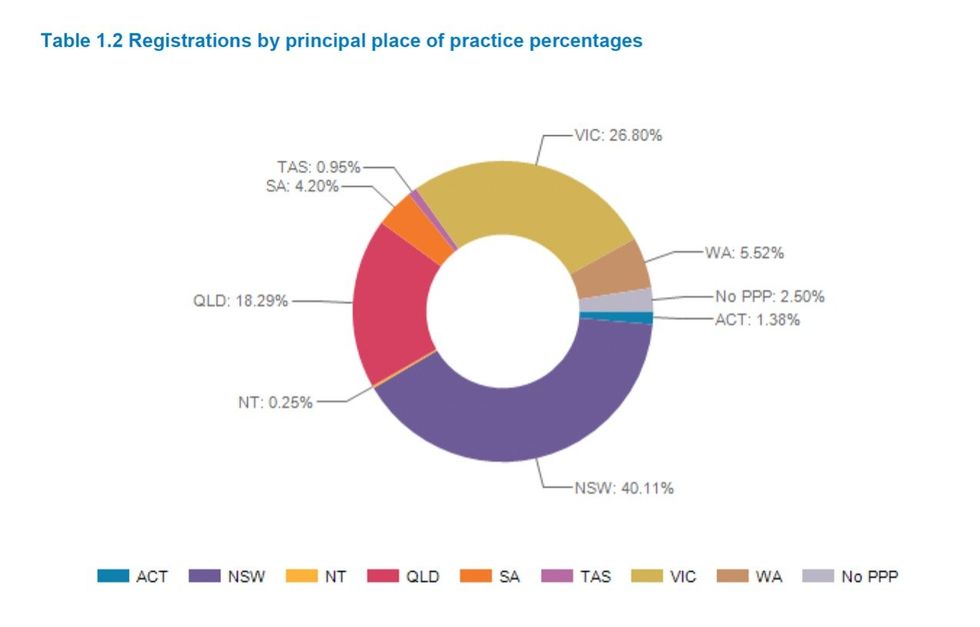

In June 2022, there were 4,839 registered TCM practitioners in Australia, with most based in NSW or Victoria, according to AHPRA's 2022 “Medical Board of Australia Registrant data” report. The majority of the practitioners were aged from 30 to 69.

"[The registration] is good for the public, but it doesn't really protect us," Leung explained. In Australia, TCM practitioners are not permitted to use the title "doctor," as that is the exclusive preserve of general practitioners and specialists.

"Chinese medicine is a freak therapy," Leung said. TCM practitioners cannot claim to "cure" patients; they can only say they can "help". As with Lamsey more than 100 years ago in the Victorian goldfields, a practitioner must not refer to herself or himself as a "doctor" or "specialist".

In addition, with so many different types of “acupuncture”, the lines are blurred. Unregistered massage therapists can do a three-day course on dry needling and then practice on clients, Leung said.

Sourcing traditional herbal treatments can also be difficult in Australia. Practitioners rely heavily on Chinese imports and Australian Customs has strict controls on the import of these herbs, with some important herbs banned. For example, the Australian Government has banned ephedra, a major herb in the Chinese medical masterpiece Treatise on Febrile Diseases Caused by Cold, because stimulant drugs can be extracted from it. Other herbs, such as fuzi, are strictly regulated and can only be used in a single dose of no more than 0.02mg, a dosage considered ineffective for treatment and thus effectively banned. Australian herbalists seek alternative herbs but Leung said their effectiveness is "completely incomparable."

As more herbal medicine and acupuncture centres open in Australia, some of the mystique of Chinese medicine is fading. Today, traditional Chinese medicine in Australia is not just about herbs, but also includes many "ready-to-use" medicines, which are made into pills and powders similar to Western medical practice. Leung said many Australian patients prefer this quick and easy medicine, without the bitter aftertaste.

Keeping the old ways

"NEXT waiting, Daniel," Mr Chan's bright and clear voice rings out again.

My session is over. As I walk out of the diagnostic room, Janet is pulling a teardrop-shaped stainless steel dustpan from under the cabinet. "Your herbs will take two hours to simmer," she said as she picked up the small brass scales to weigh them out. In the decoction room, a black ceramic pot is gurgling, steam puffing out where the lid sits only half-covering a strong-smelling, simmering soup of herbs.

I take my herbal concoction home. Once a day, five times a week, I drink a large bowl (350-400 ml) of the herbal treatment. It is so bitter that I place a straw deep in my mouth to suck up the herbal remedy, reducing contact with my tongue, and thus the bitterness on my tastebuds. After every few sips with the straw, I swallow water to wash it down.

I was told the benefits could take up to four weeks to materialise. I took it for two weeks, and in that time it did give me some relief, but the combination of a three-hour round trip to the Chatswood clinic to renew my prescription and the bitterness of the medicine made me stop. I found by following Mr Chan's advice to stop strenuous exercise, avoid most cold drinks and reduce my intake of "cold foods" such as white radish and celery, the severity of my cramps eased and I rarely need to take medication. (I keep painkillers on hand for days when the pain is more severe.)

The Chinese say "good medicine is bitter” but that bitter taste is not for everyone. Perhaps not too long from now, the overpowering scent from the decoction room, which, for thousands of years, has been intertwined with traditional Chinese medicine practice, will disappear in Australia.

Here at Mr Chan’s clinic at least, the old ways survive for now.

Tina is studying for a Master's in Journalism and Communication at UNSW Sydney. She is very interested in traditional Chinese heritage and documentaries; she loves to tell the stories of ordinary people through her writing.

As a checkout chick, I'm used to rudeness. But I can't bear the threats and violence