This is the first of five profiles in The Write Stuff series featuring literary journalists from around the world.

"One night … I stood wearing a tuxedo outside Grosvenor House, a five-star hotel on Park Lane, Central London. Downstairs in the banqueting hall I had just not won a radio award so I'd gone out for air and spotted another non-winner – the radio presenter Adam Buxton. He was leaning against some railings. I stood next to him for a while. We watched the limousines speed down Park Lane, the winners spilling out of the hotel in their tuxedos.

'You know why we always lose?' Adam suddenly said to me. I shook my head. 'Don't you see?' he said. 'You and me? We're marginal.' I looked at him. 'The things we like,' Adam continued, 'They're marginal.'

'You're right!' I said, my eyes widening. 'We are marginal!' I felt a great weight lifting. I'd spent years frantically reaching for the mainstream – but I didn't have to. It was fine. I was marginal. I could still tell those stories but they could do something else – they could de-humiliate, dignify."

-Excerpt from Frank: The True Story That Inspired the Movie

****

IF YOU'VE ever spent more than an hour on a Wikipedia page – clicking links and references, opening new tabs to look at images of the people described – then you might well say that you've gone down the rabbit hole. A sudden obsessiveness to find out every tiny detail of a subject you didn't even know existed now has you nailed to your glowing screen, and not even food or the spoils of the outside world could peel you away from getting to the bottom of the true tale.

It's hard to pinpoint exactly where Welsh journalist Jon Ronson gets his ideas and motivation from. It seems like some stories just land in his lap, like the tale of Frank Sidebottom.

Ronson played keyboard for an act, headed by a mysterious figure called Chris Sievey, in the late 1980s. Chris would put on a giant papier-mâché head and become Frank, a frontman who wasn't funny enough to be a comedy act, or musical enough to be a musical act, but sat in some awkward place in between. When the Frank head was on, Sievey was deep in character and wouldn't answer to the name "Chris", and sometimes the head stayed on far too long after the music had finished. Ronson was accepted into the band after their regular keyboard player didn't show for a gig and Ronson admitted to being able to play three chords on the piano. Cut to 2014, and the story is being made into a Hollywood film starring Michael Fassbender.

Or the time he was approached by pop star Robbie Williams, who had taken a hiatus from music to go and meet UFO abductees in Nevada. Williams wanted Ronson to chronicle the whole affair.

Some ideas seem to spring from his own fascination with the marginal, the conspiracy theorists and the kooky. The Men Who Stare at Goats (also adapted into a Hollywood film, starring George Clooney) delves into the world of paranormal pursuits adopted by the US Army in the 1970s and 1980s, where Special Forces officers started a "psychic spy unit". They would stare at goats for hours on end, with the aim of psychically stopping the goats' hearts.

Others spring from Ronson's own observations of society. For his audiobook The Butterfly Effect, which traces the consequence of the tech takeover of the porn industry, he was struck by inspiration and curiosity when he'd arranged to interview a porn performer for a different project. They were to meet in a hotel foyer, and he was surprised by a disapproving glance from the hotel clerk.

"It made me think that some people are only comfortable with porn people when they're on their computers, and not in their vicinity," says Ronson. This thought led to a deep dive into how free internet porn has affected the people who used to charge money for it, and the thought led to The Butterfly Effect and a follow-up audiobook, The Last Days of August, where a porn performer's suicide shook up the industry.

Each of Ronson's stories, even when tackling difficult subjects, has an element of comedy. Because we follow him down these rabbit holes, we're strung along by his observations of the minutia that comes along with the strange situations he finds himself in. His own anxiety is spread through each story. In 2011's The Psychopath Test, he becomes obsessed with diagnosing mental illnesses in himself and his subjects, even though he's not a qualified medical professional (bar a psychopath-spotting short course he goes on).

For each obsessive dive down the rabbit hole, Ronson puts himself directly into the story. While his thoughts and tangents might be the glue that holds complex narratives and wild ideas together, he never overshadows the subjects. As American journalist Ted Conover puts it: "A smart journalist always remembers that even though it's first person, the subject isn't me. It's them."

Though Ronson knows this, sometimes he still gets too close. On occasion, he even affects the outcome of the story he's reporting on. One example of this comes in Lost at Sea in the chapter "Blood Sacrifice" and its afterword.

Ronson has been following a cult called the Jesus Christians, who decided that the best way to show their devotion was to altruistically donate their own kidneys to patients on waiting lists in the United Kingdom and United States. It transpires that cult leader Dave McKay has agreed to be interviewed by Ronson as part of a master plan for the cult, where they spread negative propaganda about themselves, but are (in McKay's head) then vindicated by Ronson's glowing profile and the cult is then accepted by the mainstream. Ronson found out this plan half-way through reporting, and he wasn't comfortable with being a pawn in the cult's game. He wrote about the manipulation by McKay, and the story was published in The Guardian.

McKay then harassed Ronson, saying that his article was "attacking them with nasty sarcasm and underhanded belittling tactics", and that he was looking for cheap laughs and scandal. As a result of this, McKay pulled the plug on one of his cult members donating a kidney, meaning a real-life patient missed out on a potentially lifesaving procedure.

"A few weeks passed. Then I received an email from Dave in Australia. He wrote that Christine from Scotland was dying. He said he could instruct one of his members to give her a kidney, but if he did I would only accuse him of manipulation. So instead, he wrote, he had decided to let Christine die and let her death be on my conscience."

As mentioned earlier, in The Psychopath Test, he diagnoses one of his subjects as a psychopath during an interview. Not in a malicious way, but as if he were a medical expert offering up a prognosis.

While line-crossing like this may not be appropriate in most journalism, we forgive Ronson because he includes his inner monologues, which ultimately paint him as the archetypal schlemiel, a running character in the Jewish comedic tradition who is constantly finding himself in situations created by his own foolishness. But, Ronson's naivety (perhaps affected) is endearing, and it warms him to the reader. This persona makes the particularly harrowing stories digestible. He lowers his status to tease information out of his subjects, and to undermine his own position, while simultaneously challenging the collective wisdom of the political left by giving a voice to parts of society that they have marginalised.

Ronson's So You've Been Publicly Shamed points out that public shaming as a legal punishment had been phased out in the early 19th century because it was too brutal, yet the invention of Twitter has brought public shaming back into fashion, and more brutally than ever. Forget whips and stocks, we have liberal-value pile-ons, 140 characters at a time. The book chronicles how it's us, the ordinary Twitter users, the intelligentsia, the literati, the pinko lefties, who are taking part in world-wide public shaming via the popular micro-blogging site. He zeroes in on Justine Sacco, who wrote a controversial tweet that she assumed would only be seen by her 170 followers, but was retweeted by a journalist and then, she says, taken out of context. Her life was torn apart by a sardonic tweet she made before jumping on an aeroplane which was misconstrued as racist. By the time she landed, she had lost her job, been seriously threatened by strangers, and she wasn't even online to defend herself. It ruined the next chunk of her life. She was marginalised by her own cohort.

Ronson's research is detailed as ever in this account. He conducts interviews, he pulls in tweets, he references other media's perceptions of the case, he even worked out an estimate of how much money Google would have made by people looking up Justine Sacco. He loves all the little details too, and isn't afraid to try and decode Sacco's state of mind based on her appearance — always for literary effect rather than judgement. He de-humiliates his subjects. He dignifies them.

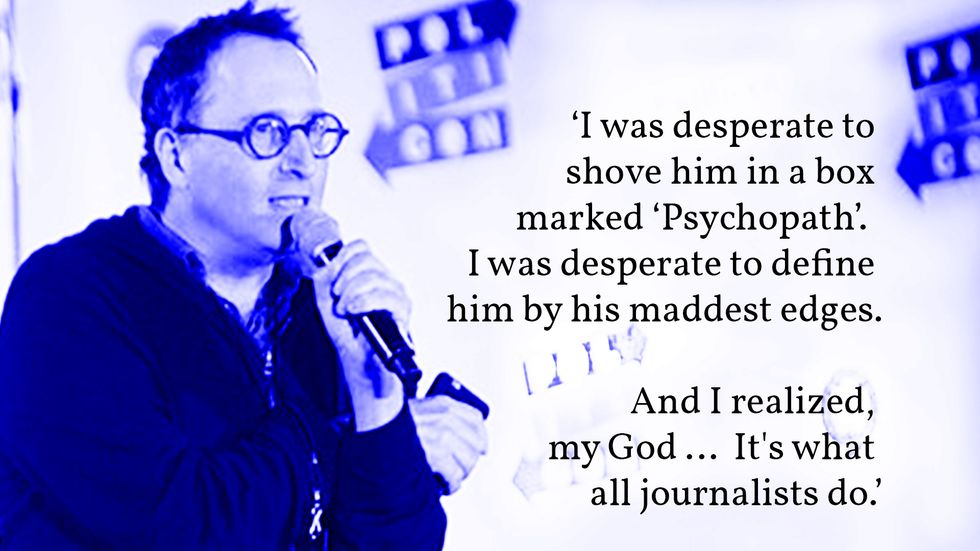

It's a pleasure joining Ronson at the margins and diving down the rabbit hole with him. It's sometimes hard to tell how much of his writing reflects the kind of life he has, or how much he sculpts his public persona towards being the kooky, fuzzy-haired conspiracy theorist with an adenoidal Welsh lilt. He offers glimpses behind the curtain to remind us of his motivations. This little epiphany, in The Psychopath's Test, came as he was meeting a corporate psychopath, trying to judge which edges of the man were psychopathic and which were "normal".

"So, whenever he said anything to me that just seemed kind of non-psychopathic, I thought to myself, well I'm not going to put that in my book. And then I realised that becoming a psychopath spotter had kind of turned me a little bit psychopathic. Because I was desperate to shove him in a box marked "Psychopath". I was desperate to define him by his maddest edges.

And I realised, my God — this is what I've been doing for 20 years. It's what all journalists do. We travel across the world with our notepads in our hands, and we wait for the gems. And the gems are always the outermost aspects of our interviewee's personality. And we stitch them together like medieval monks, and we leave the normal stuff on the floor."

Strange answers to the psychopath test | Jon Ronsonwww.youtube.com

As a checkout chick, I'm used to rudeness. But I can't bear the threats and violence