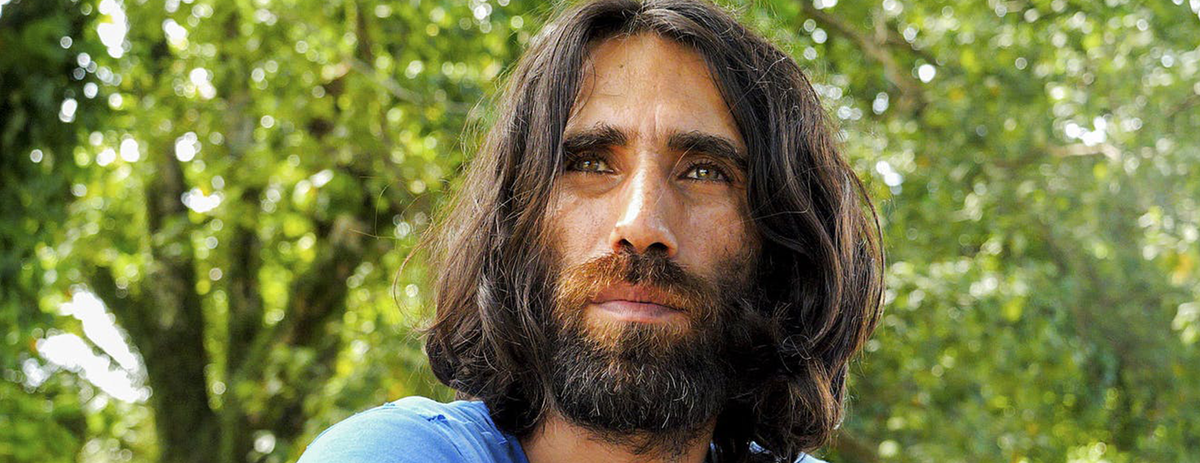

He's an award-winning novelist, a journalist, poet and filmmaker. He's a liberated prisoner – and a songbird who can't fly. Two things help sustain the high-profile offshore asylum seeker in the face of the 'cruelty of the Australian people'.

In a tiny, dark room, a group of friends are sitting on two beds. Among them, one man is pacing, telling an ancient Kurdish folk tale. He has a curious humour, and assigns roles to everyone in the group, saying, "Okay, now I say to you 'I love you, look after the children, I must go'." As he picks up his friend's bags and pretends to walk out the door, his companions descend into hysterical laughter.

As his friend, poet Janet Galbraith said, it was a rare moment of lightheartedness in a wretched life. For a moment, it was easy to forget that this room was one of many identical dorms constituting Fox Prison, in the Australian offshore processing site on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. The storyteller was Kurdish-Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani.

In 2013, Boochani fled Kurdistan under the threat of political persecution, travelling first to Indonesia, then into Australian waters on a people smuggler's boat. His boat sailed just days after then prime minister Kevin Rudd vowed in July 2013 to permanently close off access to Australia for irregular boat arrivals. So, when the boat was intercepted, all aboard were taken to Christmas Island for initial processing, and from there, Boochani and the other single men were flown to Manus Island.

'This space is part of Australia's legacy and a central feature of its history - this place is Australia itself – this right here is Australia.'

For almost six years Boochani has lived in this limbo of indefinite exile, uncertain of his visa status. His response has been to bear witness to the detainees' brutalised lives. Working for up to 12 hours a day, often in solitude, he has published articles for international media outlets, made a feature length film and written a memoir, No Friend But the Mountains, Writing From Manus Prison. It is the story of his journey towards freedom, against the odds of systemic torture and dehumanisation.

In January, the memoir won Australia's richest literary prize, the $125,000 Victorian Premier's Literary Award. In accepting the award, via video link from Manus Island, he called it a "victory for humanity" and said "I truly believe words are more powerful than this place".

Boochani, 35, has managed to consistently bear witness despite a ban on Manus detainees having mobile phones for the first three years of his detention. (The ban was overturned by a court ruling in 2016). Twice, Boochani had his mobile phone confiscated. He managed to acquire a third phone and kept it hidden from the guards inside a hole in his mattress.

He has been an active Twitter user for the past two years and he frequently posts about events unfolding on Manus. He shares his concerns for other refugees who are ill, starving and depressed and reports attempted suicides (young men hanging themselves, swallowing razor blades or using petrol to set themselves alight), he critiques Australian government policy - and he counts the days.

It was using only his phone that Boochani began to write his award-winning memoir in what he called "war-zone conditions". Laboriously and covertly, he sent his narrative, written in Farsi, via thousands of WhatsApp messages to his translators in Australia.

"Sometimes I say I was writing this book under blankets," said Boochani, in an interview with Newsworthy by WhatsApp audio from Manus Island, at the time of the book launch. "Anytime the guards could attack us and take our properties … Imagine if I would write the book on paper … writing on the phone was the best way."

The book is titled No Friend But The Mountains but is dedicated to a friend he has made during his years in detention: "For Janet Galbraith, who is a bird".

Galbraith, poet and founder of the non-profit program Writing Through Fences, was introduced to Boochani a few months after he was transferred to Manus by another asylum seeker with whom she was in contact. The pair began communicating via Facebook, bonding through their shared passion for poetry and storytelling. The tale of their friendship is a beautiful chapter within a narrative of pain and prolonged suffering.

"I don't know if you've ever experienced the development of a close friendship through writing," Galbraith said, in a phone interview from her office in Melbourne. "It allows … for an intimacy that you may not experience when you're kind of just in the same place doing the same things.

"He sings, I sing, so singing to each other and things like that meant that we had developed a very close friendship. He just bursts into song and you can imagine him on some mountain in Kurdistan just singing across the mountains."

'People unfortunately think that only when the guards hit the refugee that is torture, but the main torture is that the system is torturing people mentally.'

In 2015, when Manus Island opened to visitors, Galbraith and Boochani met in person for the first time. She has now travelled to Manus five times and acted in Boochani's film: Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time, even though, according to Boochani, she isn't an actress.

"You know, we on Manus … we have seen too much ... cruelty by Australian people," he said, "[but] we can see some people who are really ... like angels."

Galbraith and Boochani "often refer to each other as birds": he is a Pacific heron, she, a blue wren. The nomadic white-necked heron flies between Australia and Manus Island.

"One of the ways Behrouz and I connect [is] through … our reliance on nature in this world. I grew up in the bush and was quite an isolated person and most of my relationships and friendships were with animals and trees and rocks.

"I used to believe when I was quite young that I was a blue wren. I used to follow them around and for some reason I actually, honestly thought I was a blue wren."

Because of this intimacy, Galbraith knows the complex character of Behrouz Boochani better than most. "He's odd," she laughed. "Yeah, he's very odd … The image I constantly have of Behrouz is pacing, he doesn't sit still for very long. He has this direct ability to hold attention around certain things and is totally inattentive to other things. It's very incongruous.

She describes him as "incredibly intelligent", a man who has fought really hard for education.

"[He has] the ability to have some of the most incredibly detailed observations in a way that I haven't really met before. He's quite aloof around quite a few people, he's a loner, and he's very interesting creatively. Creatively, he's so prolific and constantly shifting his gaze and exploring new ways of thinking and seeing."

****

BOOCHANI'S memoir, the story of a journey that has taken him far from his beloved Kurdish mountains, is filled with stomach-churning tales of suffering and raw emotions. There are vignettes of starvation, deceit, loss and loneliness.

On Manus, Boochani explained that the lack of medical attention, the hours of hunger while queuing for meals and monthly attacks by guards at four in the morning, fostered hatred and resigned the prisoners to hopelessness. He described these experiences as being part of a Kyriarchal system, which dictated life on Manus. Borrowed from feminist theory, the term was originally coined by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza to describe how submission and domination become ingrained in social structures.

According to Boochani, "people unfortunately think that only when the guards hit the refugee that is torture, but the main torture is that the system is torturing people mentally."

Since the PNG Supreme Court ruled detention of asylum seekers on Manus Island illegal in 2016 (and the centre subsequently closed in October 2017), Boochani has been living in other accommodation on the island.

"That prison I wrote the book about, we were there for four and a half years – exactly four and a half years. We are living here [East Lorengau] about seven months," he said in August. Though nothing remains of the demolished old camp, Boochani said life has not improved - in fact, it is worse.

"The problem is not only where we are living. The problem is that people are separated from their families. People [have] lost many things over the last five years and that's why we can say that the situation is getting worse."

Nature is perhaps the one saving grace of his life on Manus. "I cannot imagine that if Manus Island were not a beautiful island, how we could survive," he said. His book fuses a romanticist's appreciation of natural beauty with an almost scientific analysis of human behaviour. Its title, No Friend But the Mountains, is a reference to Boochani's homeland, Kurdistan, where as "a child of war", the mountains provided a stronghold of refuge to him and his family.

Like many of detainees on Manus and Nauru, Boochani has not told his family details of his life in detention. "I don't want to make them worried. I think it's better that I don't engage them," he said. "I always try to protect them and say that everything's good."

The horrors of detention on Manus Island were a world away from the lecture hall at the University of NSW, Sydney where Boochani's book was launched last August. Speaking via WhatsApp audio at the launch, Boochani told his listeners then it was important that his book be read as a work of art, judged in the same way that any work by a free writer would be. The Victorian Premier's literary award underscores how fully he achieved his goal.

"Don't see me as a victim," he said. "The human rights defenders, the advocates, they always think about refugees in a romantic way. They think that the refugees are angels and other people - the racist people, they think that the refugees are evil, they are criminals … Both of these are wrong. Because we are human … This is a community, we are a community and we are like other people."

Through translator Dr Omid Tofighian, he delivered a powerful message of hope and resistance at the launch.

"I consider this book to be a victory against the system. They've tried to imprison me but in fact I'm not imprisoned. I'm free. The system couldn't take my identity. My spirit has total control over the system now … there is an escape from this prison and escape is completely natural … Escape is human."

What comes next for Boochani? For now, his future is uncertain. There is still no information about his visa status. He is one of around 1000 asylum seekers who remain on Nauru and Manus. And while he may identify with the Pacific heron, he no longer has any desire to fly to Australia.

His friend Galbraith put it this way: "Many of the people who are imprisoned [on Manus] know Australia in a much more nuanced and better way than many people who live in Australia. They know the horror and they continue to be tortured by Australia. So why would you want to come here? Why would you want to go to the hostage-holders' place?"

In his book, Boochani describes the asylum seekers' Manus existence as an extension of Australia. "This space is part of Australia's legacy and a central feature of its history - this place is Australia itself – this right here is Australia."

"I just want to get off from this island," he said, adding that he hasn't thought much about where he'd like to go. "I don't think about Australia … but when I leave this island I will leave my works for Australians."

Asked how he'd celebrate getting off Manus, ending his exile, Boochani replied: "Probably, I will sleep."

Reena is a UNSW Bachelor of Media/Laws graduate and author of The Rosella Oakshott Mysteries. She writes, draws, fences and has a (possibly unhealthy) obsession with crime fiction literature. She was a 2019 Walkley Student Journalist of the Year finalist.