Click through to Best of 2019 to discover the Newsworthy articles with greatest impact: whether by highest page views, social media engagement or winning national awards.

- Highly Commended in the 2019 Ossie Awards for student journalism category: Best text-based story by a postgraduate student (over 750 words).

I went to five Chinese daigou shops in Sydney's eastern suburbs. At each, I asked the shop assistant the same question: "Can I buy 100 cans of baby formula and deliver them to China?"

The answers surprised me. "100 cans? Why yes, you can buy 1,000 cans!" Yvette Zhang, owner of AU All Go, the only daigou shop in Maroubra, is playing on her phone and looks up to say, "just buy as much as you want".

I ask this weird question because I wonder how much the introduction of a restrictive new Chinese e-commerce law has affected the daigou industry in Australia. Given shops are still encouraging me to buy sought-after products and deliver them to China, just as before the new law was announced, it appears not much at all.

So, what is happening with this law and what's the true effect on the industry? Daigou (pronounced dye-go) is a Chinese term, which translated literally as buying on behalf of. It describes people or companies who help Chinese consumers buy overseas products. Daigou agents are often Chinese students who are studying overseas or expats who want to earn extra money.

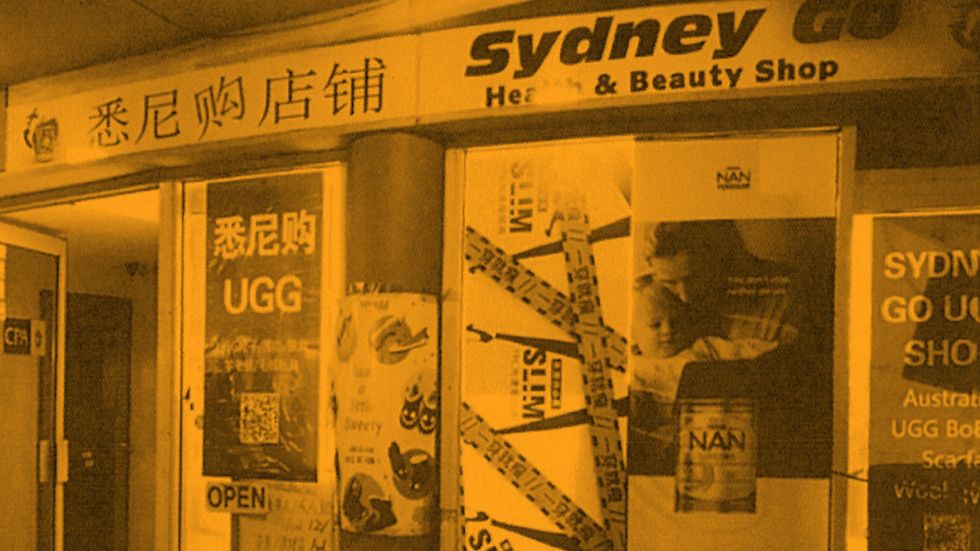

Daigou can be anybody. "This is a totally open market, there's almost no barrier to enter this market. Especially for those who live overseas but have poor English, this is an easy and attractive job that can provide support," says Allan*, who runs Sydney Go, a daigou shop on Anzac Parade, Kingsford. He graduated from the University of Newcastle with a major in accounting three years ago and went on to open his store in Sydney.

He is not alone and as the number of small operators has mushroomed, infrastructure has begun to grow up around the fledgling industry. In 2017, the Australia China Daigou Association was founded as an industry body seeking to bring Australian businesses and daigou traders together.

The key to the success of the daigou phenomenon is trust between seller and buyer. Chinese consumers often find daigou agents through friends' recommendations, popular Chinese shopping websites such as Taobao, or Chinese social media channels such as WeChat.

"No matter what the way is, trust is the key affecting consumers' choice of daigou," says Andy Wang, a research postgraduate student studying in Australia, who sees himself as a typical student daigou. He first shopped for Australian health care products for his pregnant sister in 2017. Since then he has had more pregnant customers through his sister's recommendation. "When their babies were born, they came to me to buy baby formula because they trust me."

More than a decade after the 2008 Sanlu milk scandal which killed six babies and sickened 300,000 more, demand for internationally-sourced infant formula in China remains strong. Australian suppliers are the biggest beneficiaries.

In late 2018, video of daigou scrambling to clear supermarket shelves with their large purchases of baby formula gained mainstream media coverage. Sydney Today, the biggest Australian-Chinese media platform, reported other Chinese in Australia were embarrassed and called the daigou agents "sweeping robbers".

However, supporters of the trade argue it has made a significant contribution to the Australian economy. They point to a 2017 Nielsen report, prepared in conjunction with China Road, which estimated more than 40,000 people are engaged in the Australian daigou industry, turning over roughly $100 billion annually across the retail sector.

'Daigou is already a sunset industry, we cannot stay in this area too long.'

Given these sales numbers, the opportunities for aspiring daigou appeared limitless. Then came a body blow, news of "the law of ending daigou era". On August 31, 2018, China announced the introduction of an e-commerce law, the country's first comprehensive law in the e-commerce field. It came into force on January 1, 2019.

The new law aims to regulate rapid growth of China's e-commerce market and maintain market order, according to China's official Xinhua News Agency. It said the law applies not only to Chinese online shopping platforms but also to other "e-commerce operators ... selling goods via social networks including WeChat."

Most daigous use Wechat to communicate and trade with their customers and under the new law, daigou are classified as e-commerce operators. This means the daigou industry, once in a legal blind spot, could now be constrained.

The law says:

- Daigou should have a business license in both the purchasing country and in China and fulfil their tax liability in accordance with the law;

- Foreign products without Chinese labels and products that have not passed Chinese certification cannot be sold on an online platform.

- The penalty for a breach of the law is a fine of up to 2 million RMB ($400,000).

- Further, the law makes clear provisions on sale of milk powder and healthcare products. If there is no Chinese label, and if the products are not approved by China's National Certification and Accreditation Administration, they cannot be sold.

The law has serious implications for businesses whose products were popular with daigou. Australia's a2 milk company told the Australian Financial Review, ahead of the new law's introduction, that it might affect the sales of its English-label products online, as 90 per cent a2's English-label products don't have the required State Administration for Market Regulation registration.

Student daigou Wang says the scramble for baby formula last December was due to concerns about the impact of the new e-commerce law. "[Daigou] wanted to earn quick money in the last few months," says Wang, "At that time, everyone felt that the daigou industry will be over."

The concern was valid. Three months before the law took effect, on September 28, 2018, Chinese customs sent a warning. At Shanghai's Pudong airport, at around 10pm, customs staff closed the no-declaration channel. All passengers were required to go through an X-ray security check. Hundreds of daigous were caught in the crackdown that night. It became known as "the worst day in daigou history". It was when personal anxiety turned to daigou group panic.

Daigou responded to the looming January 1 deadline in different ways. Barry Huang, a student with two years of daigou experience, chose to give up his business. "Goodbye, I won't do the daigou business from January 2019," he announced on social media. "I have no choice, the future daigou market regulation will become more and more strict, I might not be able to make any money."

Intimidated by the thought of the red tape involved in getting a business licence and unwilling to risk violating the law, he quit. A year on from "the worst day in daigou history" it's a decision he regrets.

"I definitely made the wrong decision! The law is like Schrodinger's cat, we don't know what will happen without opening the box," he says.

Meanwhile, Zhang's Maroubra daigou business is still going strong and has not been affected by the policy. She felt the same anxiety as Huang when the law was announced, but the difference was, she persisted.

"All my customers also felt anxious and asked me what will happen next. Does that mean the daigou will be over?" she recalls. "I can only give them an ambiguous answer because I don't know how this law is actually implemented, so I tell them to pick up the goods as soon as possible, because maybe I won't be able to deliver anything one day."

Zhang takes a sip of coffee and continues: "Now, I find that there's nothing at all … Today is not too busy, but there are more than 50 parcels to be sent away soon.

"You know what? I used this panic to urge my customers [to] hurry to pick up the goods and buy what they want … I didn't know what was going on. Rather, I made a fortune by relying on this matter."

'This is not the first panic, nor will it be the last time. Who knows what will happen in the future.'

Allan sees this law as the beginning of the end. "We can't control the market or policy, the only thing we can do is face it and find other ways. Daigou is already a sunset industry, we cannot stay in this area too long."

Australian brand Swisse Wellness reportedly suffered a sales downturn in Australia, as did its rival Blackmores in the first half of 2019, which it attributed to hundreds of smaller daigou operators exiting the market in the wake of the new regulations.

Laetitia Garnier, chief executive of Health & Happiness, Swisse's parent company told the Australian Financial Review in August, the company had changed its China strategy "from a passive sales model driven by individual daigou traders to a more sustainable active sales and offline model in China''.

So, will the changes be a good thing for Chinese consumers? The Chinese government says the law aims to address Chinese e-commerce market issues including "counterfeit goods, consumer fraud, privacy, intellectual property theft, tax evasion and promotion of competition and consumer protection".

Weitao Huang, a Chinese consumer who bought infant formula from Australia for his one-year-old baby, says the fear of counterfeit products in China is what drives daigou demand.

"Because China's e-commerce market environment lacks integrity, there are too many counterfeit products that the consumers can't distinguish, so I'm still worried about the product quality.

"If the e-commerce law works, consumers' rights could be guaranteed but it may also mean prices rising because of the tax [it] will add." Huang says.

****

IT IS a year since September 28, 2018, "the worst day in daigou history" and nine months since the law came into effect. The global daigou industry continues to operate, albeit with a few less players. The reason it survives, Dr Shi, professor of economics at Monash University, told ABC News, is "the law didn't take into account its enforceability".

Early in 2019, Chinese media declared if the government implemented the law, millions of daigous around the world would no longer be able to work in this grey zone and the industry would cease to exist.

In reality, the law as it relates to daigou remains murky and the messages from government mixed. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang noted, without further explanation, that implementation of the daigou part of the e-commerce law was be postponed indefinitely. Yet, according to The Wall Street Journal, eight Chinese government departments have announced they will launch "Network Sword Action" (Network Market Supervision Special Action) in the second half of 2019, to strictly regulate overseas daigou behaviour.

Zhang says it is not the first time she has heard of changes to policy that affect daigou. "Similar information appears every few years. Every time people are nervous, they feel that something big is going to happen. This is not the first panic, nor will it be the last time. Who knows what will happen in the future."

*Surname withheld.

Yifei has graduated with a Master of PR & Advertising degree from UNSW. She loves films, animals and nature (but dislikes insects). She is also interested in mindfulness and meditation and has no religious beliefs.

Afraid of an egg: the tyranny of living with social media's body standards